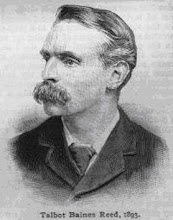

Talbot Baines Reed 1852 - 1893

This page by Jim Mackenzie

Memories of a Boyhood Friend | His Literary Career | 'The Cock House at Fellsgarth'

Talbot Baines Reed, who was born in Hackney on April 3, 1852, was the third son of Sir Charles Reed, for many years Chairman of the London School Board, and M.P. successively for Hackney and St. Ives in Cornwall.

His mother was Margaret Baines, the youngest daughter of Mr. Edward Baines, a M.P. from Leeds. Talbot’s grandfather was the well-known philanthropist Dr. Andrew Reed, a founder of the London Reedham and Infant Orphan Asylums and other notable charitable institutions.

Young Talbot was, as a small boy, under the care of Mr. Anderton at the Priory School, Upper Clapton, but at the age of thirteen entered the City of London School where the headmaster was the distinguished Dr. Abbott. Thus very early on we learn that the most notable author of boys’ public school stories was never in the great tradition of the boarding pupil and was always a “day boy”.

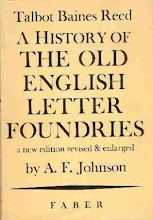

After school Talbot entered the well-known type foundry in Fann Street, a firm of which his father at that time was the senior partner. At the time of his death Talbot had progressed to being the Managing Director. Alongside his highly-rated stories for boys Talbot showed that he was the master of the type-founding craft by producing works such on English Typography which soon became the standard volumes on the subject.

Talbot married a daughter of the late Mr. S.M. Greer, a County Court Judge in Ireland and formerly the M.P. for the city of Londonderry. The couple had three children all of whom survived their father who died on 28th November, 1893.

Memories of a Boyhood Friend

When the “Boy’s Own Paper” produced their tribute to Talbot Baines Reed in the weekly edition of February 24th, 1894 they included a long section by a Mr. Vardy who had been a friend since his schooldays. He recalls his first impression of Talbot when they met at Hackney Station,

“He was a handsome boy, strong and well-proportioned, with a frank open face, black hair, and lively dark eyes, fresh expression, full of life and vigour, and with a clear ringing voice.”

Though he was never a classmate of Reed’s, being a couple of years younger, Vardy recalls the help he received when Talbot helped him to prepare for an examination by helping with a translation of Virgil’s “Aeneid”. Talbot’s translations were full of passion and energy and also replete with schoolboy slang but they brought the dusty old work to life, turning “dreary impossible history into a living and exciting romance”.

When commenting on Talbot’s sporting abilities Vardy declared that in cricket his friend was a good “all-round man”.He also informed his readers thatduring his youth in Hackney Reed founded a small cricket club and in rugby football he was also considered to be A1. His friend tells also of Talbot'sremarkable eyesight reading off signposts by the wayside when the team travelled away and none of the other fifteen players could even see the letters.

As was the custom in those days most schoolboys were known exclusively by their surnames. Not so with Reed – he was held in such affection that his initials T.B. became converted to “Tibbie” and that is how he was known amongst his close friends for the rest of his life.

Tibbie excelled in all other sports including swimming, diving, wrestling, boxing. He was a first-class shot and a prodigious long-distance walker. Twice with a companion he walked through the night from London to Cambridge, about fifty-three miles, which is a fair performance for any young man. One of these journeys in May, 1872 took place when it rained all night.

In what ever he took part Reed was always full of vigour and determination. In one of his father’s political meetings he spotted a band of agitators getting ready to storm the platform. At once he organised his brothers and friends into a wall of bodyguards and chucked the first assailant back into the crowd when he made his move.

All the Reed family were musical and Tibbie himself was very accomplished at the piano. He had a simple religious faith – he was a staunch Protestant but he could always recognise and sympathise with what was best in all forms of religion. When the signs of his approaching death began to overwhelm him he still maintained his faith, good humour and generosity.

In a little known episode in his life, whilst just seventeen, and still an uncertain swimmer himself, he was awarded the Royal Humane Society medal for saving the life of his cousin from drowning while bathing at Castlerock on the coast of Londonderry.

His Literary Career

His literary career is thought to have begun when he wrote two stories purely for the amusement of his wife. Then for the first edition of B.O.P. he submitted a story entitled “My First Football Match” which was so highly thought of that it had the honour to be placed on the first page of the first edition of the famous magazine. Reed followed this up by a series of sketches entitled “Boys of English History”.

Very soon he was appointed Special Correspondent on the Oxford- Cambridge boat race. Next he wrote a series of athletic stories such as “The Parkhurst Paper-Chase”, “The Parkhurst Boat-race” and “Parkhurst v Westfield”.

Hutchinson, the first editor of B.O.P., commented, “Indeed ‘Adams of Parkhurst’ was so real a personality to our readers that letters would reach us from captains of school and other football, boating and cricket clubs, asking us to forward their challenges to Adams, as they should like to have a turn with him and his team ! Need we say how highly amused Reed used to be on receiving these missives from us !”

In August 1879 Reed wrote his first true school story in two chapters, entitled ‘The Troubles of a Dawdler”. Again Hutchinson comments that the insight and skill shown in this unpretentious little sketch about the power of personal isolation was remarkable, for Reed seemed to have grasped the very essence of a young man who was “the very antithesis of his own resolute energetic nature.

”

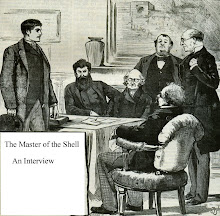

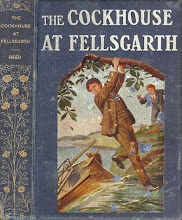

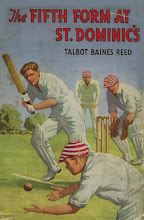

A stream of stories followed : “The Adventures of a Three Guinea Watch” in October, 1880, “The Fifth Form at St. Dominic’s” in 1881, “My Friend Smith” in 1882, “The Willoughby Captains” in 1883-4, “Reginald Craden” in 1885, “A Dog with a Bad Name” in 1886-7, “The Master of the Shell” in 1889, “Sir Ludar : A Story of the Days of Queen Bess”, in 1890, “The Cock House at Fellsgarth” in 1891 and his final book “Tom, Dick and Harry” in 1892.

Most of his stories are about public schools, and it is worth saying again that this is all the more remarkable because Reed was never other than a day boy. Others examine what happens to the pupils when they leave school and tackle life in the big city.

In his own time Reed was tremendously popular, and generous and moving tributes were paid to him after his death, Hutchinson comments, “From far-away Victoria, a girl-reader writes, ‘Not only boys, but a great number of girls out here read the B.O.P. and I like especially the stories of Mr.T.B. Reed. In the trials and struggles of “Reginald Craden” and Riddell of the “Willoughby Captains”, I have always found something to cheer and help me onward.’

To mark his passing Hutchinson wrote a detailed account of his life from which this article has drawn freely. He also republished in two instalments the harrowing tale, “The Troubles of a Dawdler”. In the same edition of “B.O.P.” from which this material was taken Hutchinson also reports the deaths of two other famous writers for boys : R.M.Ballantyne and W.H. Kingston but it is fair to say that his article on Talbot Baines Reed shows by far the greatest sense of personal loss.

The Cock House at Fellsgarth

The Cock House at Fellsgarth is almost certainly meant to be set in the English Lake District but it is better to acknowledge immediately that the landscape he creates is a purely imaginary one. “Not know Fellsgarth ? Have you never been on Hawkswater, then, with its lonely island, and the grey screes swooping down into the clear water ? And have you never seen Hawk’s Pike, which frowns in on the fellows through the dormitory window ?”

So far, a nice typical Lakeland evocation; it could even (except for the island) be a picture of Wastwater. However, in the next sentences Reed adds in details that conjure up more a school set in an Alpine valley. “I don’t ask if you have been up it. Only three persons, to my knowledge (guides and natives of course excepted), have done that. Yorke was one, Mr. Stratton was another, and the other – but that’s to be part of my story.” Indeed the Alps were well known to Reed and he had the misfortune to lose one of his brothers in a fatal mountaineering accident on the glacier near the Matterhorn.

It may safely be said that if the present reader decided to read only one public school story of the last quarter of the 19th century then The Cock House of Fellsgarth would be a remarkably good choice. It is full of energy, good humour, well-crafted plotting and an attractive narrative voice. The religious ethic is there but implicit in the behaviour of the characters and, at no times, is one subjected to moralising or preaching in order to ram the message home. Inevitably there are ill-advised climbing expeditions, disastrous outings on the lake and a fishing episode in a small boat which provides one of the mainsprings for the plot. There is even a working-class character who proves to be a rough diamond in character as well as prodigy of hard work in his studies and a whirlwind of relentless ferocity on the rugby field.

The Lakeland setting is, for the most part of the book, kept in the background and, where it emerges, is mostly used as a proving ground for the characters of the boys and young men rather than as an important feature in itself. This is an amusing and entertaining story about a community and the “Fellsgarth” of the title remains in one’s mind as a collection of individuals and their strange rules and behaviours rather than as an example of the English countryside.

Monday 20 April 2009

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)